6 Entrepreneurs Who Helped Bring New Orleans Back

Barber Wilbert “Chill” Wilson poses in his shop in New Orleans. Tim Williamson calls Chill one of the “entrepreneurial heroes of the storm.” (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

When a city closes down, everyone suddenly becomes an entrepreneur. That was the first lesson of Katrina — all of us had work to do if we wanted to restart the city. It was in those uncertain times that I saw an opportunity to validate the power of entrepreneurship. The nonprofit organization I led and still lead today, The Idea Village, believed that entrepreneurs – and those who believe in them – would recover, rebuild, and ultimately lead the next New Orleans. We just had to find them.

The Idea Village was then five years old, a young nonprofit with a successful record for running startup programs but no experience rebuilding a city. Our initial plan was simple: Give small grants to entrepreneurs who inspired us, those who could – and would – catalyze New Orleans’ rebirth. We began allocating what we called “triage grants,” ultimatly helping 130 entrepreneurs reopen for business. The individuals behind these companies we supported after Katrina – as well as others we met along the way – are among the most inspiring I have ever had the pleasure of working with.

Their drive, grit, and unparalleled determination were the building blocks for the entrepreneurial ecosystem that is thriving today. I don’t have close to enough space to acknowledge them all, so here are a few standouts. I call them the entrepreneurial heroes of the storm.

- The very first business to reopen after Katrina was Slim Goodies, a small restaurant on Magazine Street. I ate dinner with owner Kappa Horn in Baton Rouge the night before the city opened up. She said, “I’m going in.” That was that.

- Then there was Chill the barber. I met him cutting hair at a flooded gas station at Claiborne and Napoleon, using the power of a generator. He wasn’t waiting for help; he just decided to get to work. Idea Village gave him a small grant to get Mr. Chill’s First Class Cuts Barbershop reopened.

- And Leah Chase. I met Chase in her trailer outside of New Orleans institution,Dooky Chase’s Restaurant to provide a $10,000 grant. She told me that she “would stay on the battlefield until she dies.” It’s a quote I’ll never forget; it still give me chills.

Chef Leah Chase stands outside her famous Creole restaurant, Dookie Chase’s. (AP Photo/Cheryl Gerber, file)

- We were fortunate to support four incredible female entrepreneurs known as the Belles of Bayou Road, led by Vera Warren Williams of Community Book Store. They were the catalyst that brought Bayou Road back to life after the storm. Their motto: “when spider webs unite, they can tie up a lion.”

- In some cases, all people needed was a small grant and a little bit of advice. I remember meeting with Loretta from Loretta’s Pralines. She just needed a little money to buy supplies so she could deliver pralines during the Christmas Season after Katrina. It makes me smile every time I see her at Jazz Fest.

- Local entrepreneur Jonathan Ferrara approached The Idea Village in 2007 to help support local artists. We decided to partner on what we called the “Artdocs” program and strategically allocated $41,000 to 40 artists specifically so they could buy supplies at local small businesses.

It’s not just the entrepreneurs that deserve recognition, but those who believed in them – and the sense of possibility – early on. As Atlantic reporter Derek Thompson wrote in 2013, “Sometimes a start-up city is just a city getting started, again.” Today, entrepreneurial activity in the city is currently 64 percent above the national average, according to Brookings Institution. I’d say New Orleans is well on its way to becoming the hub of entrepreneurship in the South.

But as the recovery story of New Orleans continues to be written, there should be a long chapter on the entrepreneurial talent who took the reins right after Katrina, those people who believed it was possible when it seemed impossible.

Tim Williamson is Co-founder and CEO of The Idea Village .

The Trouble With Fretting Too Much About Brain Drain

(AP Photo/Jessica Hill, File)

Back in 1999, the Pittsburgh Regional Alliance came up with an idea to curb brain drain. A fictional character named Border Guard Bob, a Barney Fife-type patrolman in uniform, would appear in ads doing things like hitching a bungee cord to the back of people’s car bumpers and telling folks to “Look before you leave.” It was a marketing ploy to prevent residents, particularly young people and those who had come to Pittsburgh to study at one of its universities, from relocating.

Though the anticipated multimillion-dollar TV campaign never rolled out, Border Guard Bob is symbolic of the befuddling, often expensive ways in which cities try to retain their “best and brightest” young workers. Practically every city has complained at some point about the existential threat of brain drain. Michigan created a $100 million “cool cities” initiative in 2003 to redevelop loft spaces that would “retain and attract” a creative class. Philadelphia set out to create thousands more internships a year to stimulate retention of recent grads. UpDayton was founded for the sole purpose of studying and reversing the Ohio city’s brain drain.

Yet, look at current data, and you might start to think cities today are fighting a phantom. And furthermore, the funds they may spend on the battle could be directed to creating more equitable cities for all residents.

An exodus of educated people is an urban legend in almost every instance, according to a new paper called “Brain Gain in America’s Shrinking Cities” by Aaron Renn of the right-leaning think tank the Manhattan Institute. “I don’t think these were all stupid programs, but the problem they were designed to attack is not as serious as they think,” says Renn. He’s not the first to make a case that cities’ handwringing over brain drain numbers is problematic. In a paper released last year, the Boston Redevelopment Authority argued that “neither ‘brain drain’ nor ‘retention’ is a good indicator of how well Boston’s economy performs with regard to its need for younger, college-educated workers.”

An oft-used metaphor regarding Midwest cities is that hemorrhaging young talent is like a leaky tub, with grads flowing to glitzier economies in New York, Silicon Valley and Boston. Renn disputes the notion in his paper, writing, “What this mind-set misses is the running tap at the top of the tub. Though there may be some leakage, the water level (the number of residents with college degrees) is rising.”

He analyzed demographic data from America’s 28 largest “shrinking” cities — those that fit the criteria of being both one of the country’s 100 largest and having experienced measurable population loss and/or job loss — and he says he found the popular rhetoric surrounding brain drain to be misguiding and simplistic. Between 2000 and 2013, the amount of adults with a bachelor’s degree or better grew substantially — by at least double digits — in all 28 metros; in terms of 25- to 34-year-olds, 20 out of the 28 witnessed double-digit gains in degree holders, with only three (Bridgeport, Detroit and Toledo) registering declines.

Further, Renn found that roughly half of the 28 shrinking cities gained more degree holders than the national average over that span. “I was really impressed to find places like Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Buffalo all go from less educated than America as a whole to more educated.”

Take Buffalo, for example. Renn says the city gained more than 53,000 adults with college degrees, even while it lost 33,000 residents overall. The juxtaposition explodes the notion that brain drain is happening there at all (when in fact, the city ranked in the top 10 gainers among U.S. metros when it came to degree holders over that span), and it also overturns the idea that losing an educated class is an inherent occurrence of deindustrialization.

Upon studying IRS tax return data, Renn found that the Buffalo metro area has the lowest out-migration rate of any major city in the United States. Meanwhile, it has a shrinking job base, a 30 percent poverty rate and a host of other problems — brain drain just doesn’t happen to be one of them.

“I would argue that a lot of these places suffer from too little out-migration, not too much,” says Renn. They’ve become “demographic cul-de-sacs” lacking the dynamism needed to spur more innovation and economic reinvention like what’s occurred in the city of Boston.

What, then, explains the drastic disconnect between the perceived existence of brain drain and the reality Renn reveals? More than anything, it’s how we’ve inaccurately framed the conversation. The most common measuring stick for brain drain has been retention rate, a topic that’s been researched nationally quite little and yet is quoted ad nauseam by local politicians. Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed complained last year about a 50 percent retention rate out of Georgia Tech.

The coveting of millennials is unlikely to fade, but Renn’s paper is a call for city officials to think hard about how many resources they are directing toward keeping what they consider to be their shining stars.

“Fixing your streets, rehabbing your parks,” Renn says, “there’s a lot that can be done with that money instead.”

For him, the broadest concern about misdiagnosing brain drain has nothing to do with misapplied metrics. It’s about the financial and political capital that’s been committed to an overblown problem.

“When you’re focused exclusively on retaining people with college degrees, you’re focusing a lot on problems of the elite,” says Renn. “But that battle is already won. Let’s turn our attention to more pressing problems, like providing opportunities in impoverished urban neighborhoods that have been left behind.”

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Malcolm is a Next City 2015-2016 equitable cities fellow. He has contributed writing and research for The Atlantic and Philadelphia magazine, among other publications. He’s appeared on NPR’s “On The Media” and “All Things Considered.” He lives in Philadelphia.

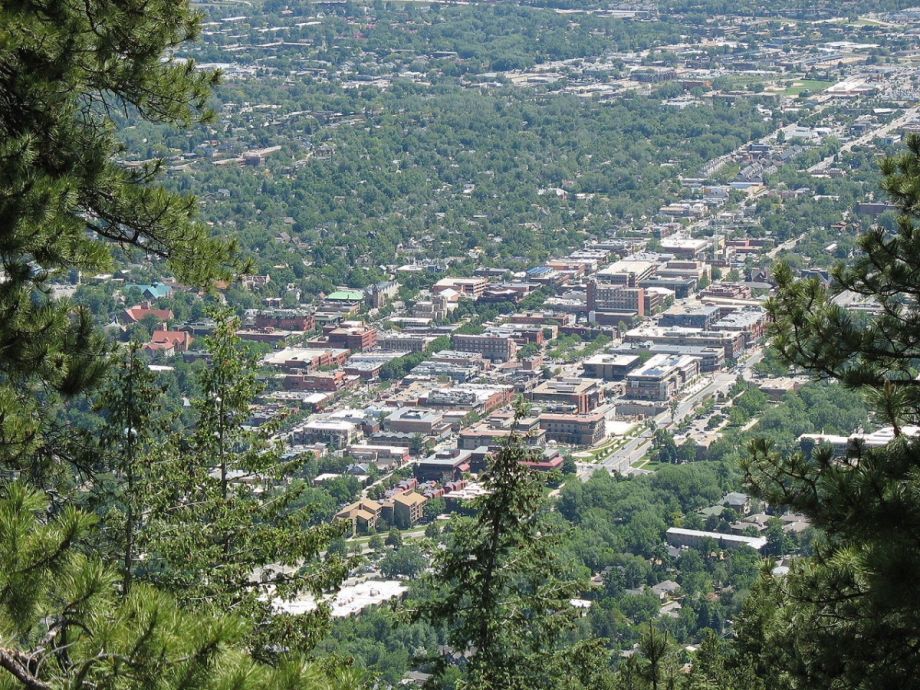

Boulder Will Use Big Data Program to Monitor Trees

Boulder, Colorado, will use a new software to judge the efficacy of tree cover conservation work. (Photo by Teofilo)

As cities around the world work toward a more sustainable and resilient future, a new wealth of satellite and aerial imagery can be a powerful aid — if officials have the tools to interpret the visual data.

“[Imagery] is easy to gather and very difficult to extract data from,” says Rick Gosalves, local government market manager at geospatial and positioning software company Trimble. “Images offer a massive amount of data. If you can make sense from massive data you can make smart data.”

Trimble’s eCognition Essentials software analyzes readily available aerial and satellite imagery to produce data about land use that can be used for GIS mapping. eCognition can be programmed to classify any number of ground covers, from permeable and impermeable surfaces to grassland, as well as areas with flooding or fire damage.

“If you’re human and you can determine what’s in the image, you can program the computer [with this software] to figure out and extract what it is,” says Gosalves.

Last week, Trimble announced a partnership with the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities (100RC) initiative, a project that provides municipalities with financial, logistical and technical support to achieve resiliency and sustainability goals. The eCognition software, plus support and training on how to use it, will be made available for free to all 100RC cities if it can help further their resiliency goals.

Boulder, Colorado, will be the first city to work with Trimble. The city hired its first chief resilience officer through 100RC a year ago.

As part of its resiliency plan, Boulder is trying to better evaluate the health of its urban canopy and ways to retain and manage it. Urban forests not only remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but they also remove other air pollutants like sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide, and save energy by lowering local temperatures. According to Boulder’s Urban Forestry Department, trees in the city also reduce stormwater runoff by approximately 422 million gallons per year, performing a service valued at $5.58 million.

eCognition will help map that tree cover: where it is, where it is damaged and where it can be strengthened. The software analyzes visual data, but doesn’t collect it, so Trimble will work with a handful of other companies to provide a complete picture. DigitalGlobe might provide the high-resolution satellite imagery, for example, and Esri might provide a repository for GIS data. Then eCognition can be programmed to seek out healthy or damaged canopy, allowing officials in Boulder to judge the efficacy of conservation projects.

Trimble joins over 50 private, public, academic and nonprofit partners that provide services, software and guidance to cities in the 100RC network. One of the primary goals of the initiative is to connect cities with technical resources to implement their stated resiliency goals.

“One of the key challenges we have seen is that cities don’t know about these opportunities,” says Liz Yee, 100RC’s vice president of strategic partnerships and solutions. “What our platform intends to do is not to solve the entire chain of challenges from start to finish but to really provide cities with the accelerators they need to become more resilient.”

While Trimble will provide training and support, the eventual goal is for cities like Boulder to be able to use tools like eCognition on their own. And for early adopters of the software to become an example for other 100RC cities with similar resiliency projects.

“A lot of data collected today, whether it’s sitting in a GIS somewhere or whether it’s sitting in a hard drive on someone’s desk, [we want] to unlock that data,” says Gosalves. “The really nifty thing is the chance for cities to actually diagnose and use that information to make decisions, better decisions.”

The Works is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Satellite Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. See her work at jakinney.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered